Marlene’s Interest in Race

My interest in race began when we moved to Deal Park. I was thirteen and in my final year of grammar school. Before that, we lived in Belmar, a tiny town, approximately one square mile. The small Black population largely lived within a one block area along the western border of town. My grandparents lived on the block where the Black neighborhood began. The grammar school that I attended was integrated, primarily because we had only one class per grade. I went to school with Black children and because I walked to my grandparents’ house for lunch when school was in session, I walked to and from school with Black classmates. Although none of my Black classmates visited my home (my white Christian school friends didn’t either), I spent time playing with them at recess. So it was odd for me when we moved to Deal Park, a fully segregated community. Not only were there no Black families living in Deal Park, but unknown to me, many adults in town worked together to ensure that Blacks could not buy property there. In my last year of grammar school, 8th grade, I had no Black classmates. The absence of race made me begin to think about race.

Ashbury Park High School

Although Deal Park was part of a new regional school district, the high school was still under construction, and students continued to attend Asbury Park High School (APHS), which was integrated. APHS had a substantial number of Black students but only one Black boy was in my classes. At that time, students were tracked by professional interests (college, business, vocational/technical) and academic ability, which was apparently assessed by a standardized test and prior grades. Few Black students were in the college track, and only one was in the advanced academic track that I was in. Even though I was beginning to develop a consciousness about race, I never questioned why my Black classmates weren’t in academic classes with me (we did attend homeroom and gym classes together).

Althea Gibson

Our house in Deal Park was directly across the street from the Deal Golf and Country Club, which didn’t allow Jews or Blacks. As a Jewish family, we talked about this a lot. When Althea Gibson, the Black tennis champion, retired from tennis, she joined the professional women’s golf tour. One of my most powerful memories from our years in Deal Park was watching a helicopter land on the driving range across the street to drop off Gibson who was playing in a tournament. This was not because she was a celebrity but, rather, because of racism: Althea Gibson wasn’t allowed to use the clubhouse or any facilities because she was Black.

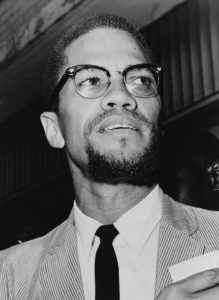

Malcom X

When I was fifteen, I went to New York with friends and snuck into the Les Crane Show (I was underage), a television talk show. Malcolm X was the guest that night in one of his last appearances before he was assassinated. I was captivated by this tall, soft-spoken Black man. His ideas seemed reasoned and reasonable. He didn’t espouse violence by Blacks; rather, he said Blacks had the right to defend themselves in situations where the police and other law enforcement did not protect them. The man I listened to that night was in every way unlike the man I read about in the news.

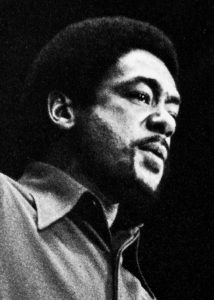

Bobby Seale

In college I took a course in “The Rhetoric of the Black Power Movement.” I read The Autobiography of Malcolm X and Bobby Seale’s Soul on Ice. A friend gave me Claude Brown’s Manchild in the Promised Land. These books gave me a glimpse into the lives of Black Americans and made me aware of the racial discrimination they faced. I was so moved by Seale’s rhetoric that I wrote my master’s thesis on the trial of the Chicago Eight, who were charged with conspiracy to incite a riot at the 1968 Democratic Convention. Seale was tried separately from his seven white co-defendants, and I focused my thesis primarily on a comparison of the language of Seale and the presiding judge, Julius Hoffman, concluding that they—as Black and white men– had different experiences and world views. Yet, despite all of my reading and writing about race, I still hadn’t made a connection to my own life and how my privilege both shielded me and made me complicit in perpetuating racial inequities.

I continued to write and teach about race as my career progressed but didn’t fully see my role in maintaining white supremacy until Fern and I adopted our sons, one in 1989 and the other in 1991. The experience of becoming an interracial family and parenting Black sons taught us about white privilege and about the myriad ways that Blacks confront racism in education, criminal justice, health care, and simply living day-to-day. Yes, I was still a white person shielded by white privilege. But I began to see how racial identity was shaping our young sons’ lives. When the boys were young, they were often protected by our white privilege, but as they ventured out on their own, without our protection, we began to see the stark outline of racism in their lives.